Culture of Meghalaya

Cultural Overview

All cultures have unique facets and aspects, but the three main tribes of Meghalaya have a cultural practice that is found in few other communities across India-the matrilineal structure of the families. Simply put, this is a system in which the woman is the custodian of the family. After their wedding, her husband moves into her home. Their children trace their linage through the mother’s bloodline and take her clan’s name as theirs. Additionally, the mother’s ancestral property is passed down to the khun khatduh (youngest daughter) of the house, who usually continues to live in it even after she gets married.

Due to the abundant rain that Meghalaya receives, its landscape crisscrossed with rivers and dotted with lakes and ponds. Not surprisingly, fishing is not just an occupation but also a popular form of recreation. And the locals take it very seriously indeed. Angling competitions are very popular here, and anglers travel across the state to participate in them. The stakes are high and prizes are often in the six figures!

All cultures have unique facets and aspects, but the three main tribes of Meghalaya have a cultural practice that is found in few other communities across India-the matrilineal structure of the families. Simply put, this is a system in which the woman is the custodian of the family. After their wedding, her husband moves into her home. Their children trace their linage through the mother’s bloodline and take her clan’s name as theirs. Additionally, the mother’s ancestral property is passed down to the khun khatduh (youngest daughter) of the house, who usually continues to live in it even after she gets married.

Due to the abundant rain that Meghalaya receives, its landscape crisscrossed with rivers and dotted with lakes and ponds. Not surprisingly, fishing is not just an occupation but also a popular form of recreation. And the locals take it very seriously indeed. Angling competitions are very popular here, and anglers travel across the state to participate in them. The stakes are high and prizes are often in the six figures!

Language and Dialects

English is the official language and is widely spoken in urban centres, while Khasi and Garo are the other main languages. An aspect of Khasi that an English speaker might find fascinating is that its script is based on the alphabet they know, but it has only twenty-three letters. Khasi was an oral language with no script of its own until 1841, when a Welsh missionary named Thomas Jones arrived in Sohra and wrote the alphabet in the Latin script for the first time, modifying it for phonetic accuracy.

English is the official language and is widely spoken in urban centres, while Khasi and Garo are the other main languages. An aspect of Khasi that an English speaker might find fascinating is that its script is based on the alphabet they know, but it has only twenty-three letters. Khasi was an oral language with no script of its own until 1841, when a Welsh missionary named Thomas Jones arrived in Sohra and wrote the alphabet in the Latin script for the first time, modifying it for phonetic accuracy.

Art & Handicrafts

Rooted in deep cultural heritage and tribal expression, Meghalaya’s arts and crafts mirror the region’s vibrant soul, much like its celebratory festivals. The state’s artisans are renowned for bamboo and cane craftsmanship—seen in intricately woven baskets, mats, and furniture that blend function with artistry. Weaving is equally important, especially among the Khasi, Jaintia, and Garo communities, where traditional handlooms produce vibrant textiles and shawls bearing tribal motifs. Bamboo and cane craftsmanship form the backbone of Meghalaya’s artisanal heritage, with the Khasi, Garo, and Jaintia tribes each showcasing unique styles.

Among the Khasis, items like the Khoh (conical basket), Knup (bamboo rain shield), and intricately woven mats are common household essentials. These are not only practical but also skillfully designed, reflecting their deep-rooted connection to nature. The Garos excel in basketry and a technique called poker work, where designs are artistically burnt onto bamboo surfaces using heated metal rods. Their crafts range from sturdy storage containers to decorative panels. The Jaintias, meanwhile, are known for their finely woven Tlieng mats—renowned for both their durability and intricate patterns—as well as fish traps and utility baskets used in daily life. As for textiles, the Garo tribe stands out for its vibrant handwoven fabrics, especially the Dakmanda, created using backstrap looms. These textiles often feature bold geometric designs and are dyed using local natural pigments. The Khasis, though less active in weaving today, maintain traditions through the Jainsem, a draped garment for women, and Ryndia—eri silk woven and dyed sustainably in villages like Umden.

Among the Jaintias, weaving is done using loin looms, producing variations of traditional garments like the Jainkup, often in subdued tones suited to everyday and ceremonial use. Together, these crafts represent a tangible link to tradition, community, and creative resilience across Meghalaya’s hills. Wood carving, musical instruments, beadwork, and intricate silver jewelry also play a role in storytelling and ritual. Much like Meghalaya’s festivals, its crafts aren’t just aesthetic—they are a celebration of identity, passed down through generations and reimagined in modern contexts.

Rooted in deep cultural heritage and tribal expression, Meghalaya’s arts and crafts mirror the region’s vibrant soul, much like its celebratory festivals. The state’s artisans are renowned for bamboo and cane craftsmanship—seen in intricately woven baskets, mats, and furniture that blend function with artistry. Weaving is equally important, especially among the Khasi, Jaintia, and Garo communities, where traditional handlooms produce vibrant textiles and shawls bearing tribal motifs. Bamboo and cane craftsmanship form the backbone of Meghalaya’s artisanal heritage, with the Khasi, Garo, and Jaintia tribes each showcasing unique styles.

Among the Khasis, items like the Khoh (conical basket), Knup (bamboo rain shield), and intricately woven mats are common household essentials. These are not only practical but also skillfully designed, reflecting their deep-rooted connection to nature. The Garos excel in basketry and a technique called poker work, where designs are artistically burnt onto bamboo surfaces using heated metal rods. Their crafts range from sturdy storage containers to decorative panels. The Jaintias, meanwhile, are known for their finely woven Tlieng mats—renowned for both their durability and intricate patterns—as well as fish traps and utility baskets used in daily life. As for textiles, the Garo tribe stands out for its vibrant handwoven fabrics, especially the Dakmanda, created using backstrap looms. These textiles often feature bold geometric designs and are dyed using local natural pigments. The Khasis, though less active in weaving today, maintain traditions through the Jainsem, a draped garment for women, and Ryndia—eri silk woven and dyed sustainably in villages like Umden.

Among the Jaintias, weaving is done using loin looms, producing variations of traditional garments like the Jainkup, often in subdued tones suited to everyday and ceremonial use. Together, these crafts represent a tangible link to tradition, community, and creative resilience across Meghalaya’s hills. Wood carving, musical instruments, beadwork, and intricate silver jewelry also play a role in storytelling and ritual. Much like Meghalaya’s festivals, its crafts aren’t just aesthetic—they are a celebration of identity, passed down through generations and reimagined in modern contexts.

Music and Dance

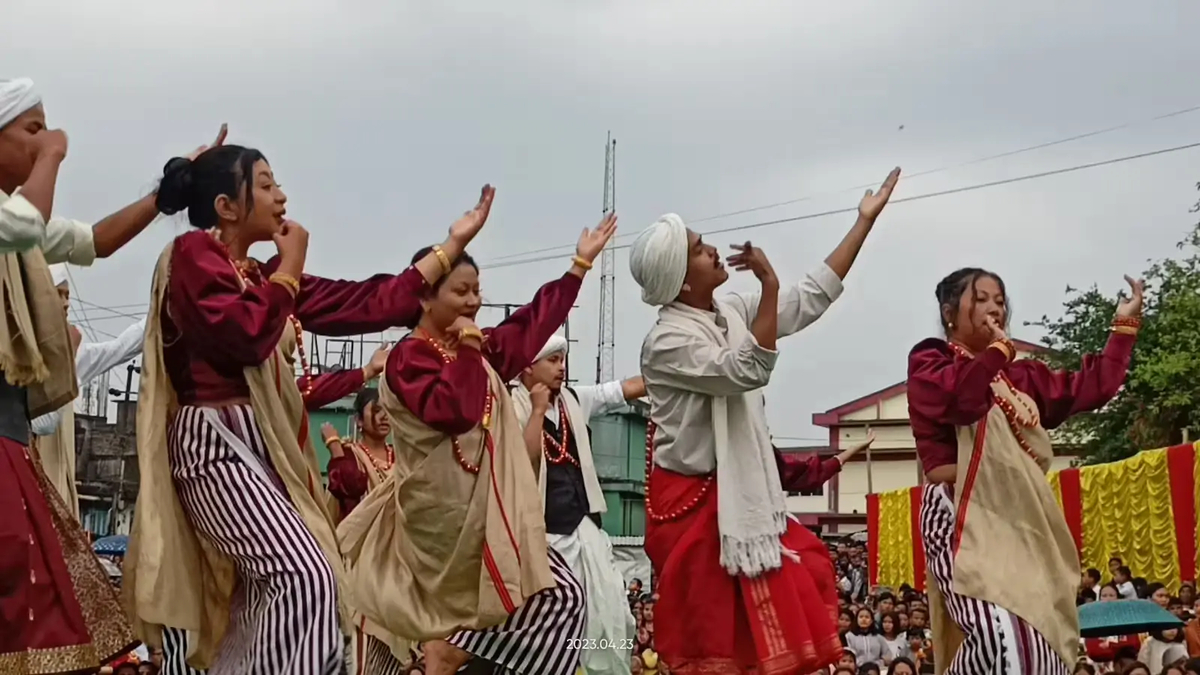

Music and dance are the heartbeat of Meghalaya’s tribal identity, echoing through hills and valleys in rhythmic celebration. In Khasi culture, traditional instruments like the duitara (a four-stringed lute), tangmuri (a high-pitched wind instrument), ksing (drums), besli (flute), and padiah (a single-faced drum) create the musical backdrop for dances such as Shad Suk Mynsiem, a graceful celebration of fertility and peace; Shad Kynjoh, performed during house-blessing ceremonies, invoking protection and prosperity; and Pom-Blang Nongkrem, a ritual dance linked to royal heritage and harvest blessings. Chant-like phawar songs add a poetic layer to these performances.

The Jaintias share similar instruments, including the sharati (reed pipe), ksing padiah, and marynthing (string instrument). Their dances—like Chad Sukra, performed before sowing to invoke divine blessings; Lahoo Dance, a social dance performed by both men and women, often during festivals and weddings; and Chad Pastieh, held post-harvest, essentially a thanksgiving dance symbolizing community unity. Behdienkhlam, the most significant Jaintia festival, features a powerful dance ritual where men symbolically drive away disease and misfortune by striking rooftops and dancing in sacred pools with decorated structures called rots. Lyrics often draw from oral folklore and spiritual beliefs.

In the Garo Hills, music is percussive and deeply communal. Instruments like the nagra (large drum), adil (bamboo flute), and rang (buffalo horn) set the stage for spirited dances such as Wangala, a dance that celebrates harvest with synchronized drumming, horn blowing, and vibrant attire; Doroa, a social dance performed during weddings or gatherings, emphasizing communal joy and graceful footwork; and Chambil Moa, also called the Pomelo Dance, which involves complex steps while holding a pomelo, showcasing dexterity and festivity. Do Dru Sua is another garo dance performed by men to showcase valor and strength, often accompanied by chants and dramatic gestures. These art forms are more than entertainment—they are vessels of memory, identity, and resistance. They preserve oral traditions, reinforce social values, and connect generations. Whether performed in sacred groves, village courtyards, or modern stages, Meghalaya’s music and dance continue to evolve while staying rooted in the land’s spiritual and cultural ethos.

Music and dance are the heartbeat of Meghalaya’s tribal identity, echoing through hills and valleys in rhythmic celebration. In Khasi culture, traditional instruments like the duitara (a four-stringed lute), tangmuri (a high-pitched wind instrument), ksing (drums), besli (flute), and padiah (a single-faced drum) create the musical backdrop for dances such as Shad Suk Mynsiem, a graceful celebration of fertility and peace; Shad Kynjoh, performed during house-blessing ceremonies, invoking protection and prosperity; and Pom-Blang Nongkrem, a ritual dance linked to royal heritage and harvest blessings. Chant-like phawar songs add a poetic layer to these performances.

The Jaintias share similar instruments, including the sharati (reed pipe), ksing padiah, and marynthing (string instrument). Their dances—like Chad Sukra, performed before sowing to invoke divine blessings; Lahoo Dance, a social dance performed by both men and women, often during festivals and weddings; and Chad Pastieh, held post-harvest, essentially a thanksgiving dance symbolizing community unity. Behdienkhlam, the most significant Jaintia festival, features a powerful dance ritual where men symbolically drive away disease and misfortune by striking rooftops and dancing in sacred pools with decorated structures called rots. Lyrics often draw from oral folklore and spiritual beliefs.

In the Garo Hills, music is percussive and deeply communal. Instruments like the nagra (large drum), adil (bamboo flute), and rang (buffalo horn) set the stage for spirited dances such as Wangala, a dance that celebrates harvest with synchronized drumming, horn blowing, and vibrant attire; Doroa, a social dance performed during weddings or gatherings, emphasizing communal joy and graceful footwork; and Chambil Moa, also called the Pomelo Dance, which involves complex steps while holding a pomelo, showcasing dexterity and festivity. Do Dru Sua is another garo dance performed by men to showcase valor and strength, often accompanied by chants and dramatic gestures. These art forms are more than entertainment—they are vessels of memory, identity, and resistance. They preserve oral traditions, reinforce social values, and connect generations. Whether performed in sacred groves, village courtyards, or modern stages, Meghalaya’s music and dance continue to evolve while staying rooted in the land’s spiritual and cultural ethos.

Architecture & Heritage

Steeped in indigenous culture and traditional aesthetics, Meghalaya’s architecture and heritage reflect the intimate relationship between communities and their environment. In the Khasi and Jaintia hills, traditional homes were often built using bamboo, wood, and stone, elevated on stilts to withstand heavy rain. Traditionally, the Khasi and Jaintia people embraced their own indigenous architectural style, often utilizing the abundant bamboo and timber found in the Khasi Hills.

However, in recent times, most have transitioned to building homes with modern materials like bricks and cement. Sacred groves like Mawphlang preserve ancient rituals and ecological wisdom, while monoliths dot the landscape, commemorating ancestors and marking historical events. The Jaintias are particularly known for their megalithic heritage in Nartiang, where a collection of towering stones forms one of the largest megalithic sites in the region. Their settlements were typically nestled in forested hills, with sacred groves and clan altars reflecting deep spiritual ties to nature and animist beliefs. Garo architecture can be partitioned into nokmong (Main family home) , nokpante (Bachelor dormitory), jamsreng (Field storage hut), and jamatal (small jhum field shelter).

The Garo Hills are dotted with sacred sites, including Nokrek Peak and traditional village gates, which serve both spiritual and communal function. Architectural features such as wooden carvings and earth-toned facades also convey spiritual beliefs and communal values. Together, these structures are more than buildings—they are living testaments to tradition, echoing the stories and resilience of Meghalaya’s people.

Steeped in indigenous culture and traditional aesthetics, Meghalaya’s architecture and heritage reflect the intimate relationship between communities and their environment. In the Khasi and Jaintia hills, traditional homes were often built using bamboo, wood, and stone, elevated on stilts to withstand heavy rain. Traditionally, the Khasi and Jaintia people embraced their own indigenous architectural style, often utilizing the abundant bamboo and timber found in the Khasi Hills.

However, in recent times, most have transitioned to building homes with modern materials like bricks and cement. Sacred groves like Mawphlang preserve ancient rituals and ecological wisdom, while monoliths dot the landscape, commemorating ancestors and marking historical events. The Jaintias are particularly known for their megalithic heritage in Nartiang, where a collection of towering stones forms one of the largest megalithic sites in the region. Their settlements were typically nestled in forested hills, with sacred groves and clan altars reflecting deep spiritual ties to nature and animist beliefs. Garo architecture can be partitioned into nokmong (Main family home) , nokpante (Bachelor dormitory), jamsreng (Field storage hut), and jamatal (small jhum field shelter).

The Garo Hills are dotted with sacred sites, including Nokrek Peak and traditional village gates, which serve both spiritual and communal function. Architectural features such as wooden carvings and earth-toned facades also convey spiritual beliefs and communal values. Together, these structures are more than buildings—they are living testaments to tradition, echoing the stories and resilience of Meghalaya’s people.

Clothing

While modern fashion has woven its way into everyday life across Meghalaya, the people of the state continue to take pride in their traditional attire—often worn during festivals, rituals, and community gatherings. The clothing of the Khasi, Jaintia, and Garo tribes is deeply tied to their environment, beliefs, and social customs, with each district reflecting its own unique sense of identity and artistry.

In Khasi Hills, traditional Khasi attire reflects both utility and grace. Women wear the Jainsem, a two-piece cloth draped over the shoulders and fastened at the front. During ceremonial occasions, it is often paired with a tapmohkhlieh (head cloth), ornate gold or coral jewellery, and silver chains across the chest. A more elaborate version, the Dhara, is worn during dances like Shad Suk Mynsiem, where the voluminous silk drapes are richly embroidered.

Khasi men traditionally wear a sleeveless vest, a dhoti, and a turban, though during festivals, the attire is enhanced with a sword, ornamental jacket, and headgear adorned with feathers, especially by male dancers.

The Jaintia women's clothing is similar to the Khasis but distinguished by finer detailing and brighter hues. The Yuslei (turban-like headwrap), Thoh Khyrwang (draped cloth), and decorative coral beads create a striking ensemble during festivals like Behdeinkhlam. Women wear multiple layers of cloth wrapped around the waist and torso, and often adorn themselves with heirloom jewellery passed down through generations.

Jaintia men, particularly during festive processions, wear traditional dhotis and headgear, often carrying symbolic items such as wooden clubs or flags during ceremonial dances. The attire is both symbolic and spiritual, reflecting the tribe’s devotion and cultural pride.

Traditional Garo attire stands out with its vibrant colours and intricate weaves. Garo women wear the Dakmanda, a handwoven wraparound skirt tied at the waist, often paired with a blouse and the Daksari, another length of cloth draped over the shoulder. Traditional jewellery made from beads, brass, and silver completes the look, especially during dances like Wangala.

Men wear the Nokma Chikna, a cloth tied around the waist, and often carry spears or horns during cultural performances. Feathered headgear, necklaces made of boar tusks, and traditional bags enhance the ceremonial attire, which often signifies the wearer’s clan and status.

While modern fashion has woven its way into everyday life across Meghalaya, the people of the state continue to take pride in their traditional attire—often worn during festivals, rituals, and community gatherings. The clothing of the Khasi, Jaintia, and Garo tribes is deeply tied to their environment, beliefs, and social customs, with each district reflecting its own unique sense of identity and artistry.

In Khasi Hills, traditional Khasi attire reflects both utility and grace. Women wear the Jainsem, a two-piece cloth draped over the shoulders and fastened at the front. During ceremonial occasions, it is often paired with a tapmohkhlieh (head cloth), ornate gold or coral jewellery, and silver chains across the chest. A more elaborate version, the Dhara, is worn during dances like Shad Suk Mynsiem, where the voluminous silk drapes are richly embroidered.

Khasi men traditionally wear a sleeveless vest, a dhoti, and a turban, though during festivals, the attire is enhanced with a sword, ornamental jacket, and headgear adorned with feathers, especially by male dancers.

The Jaintia women's clothing is similar to the Khasis but distinguished by finer detailing and brighter hues. The Yuslei (turban-like headwrap), Thoh Khyrwang (draped cloth), and decorative coral beads create a striking ensemble during festivals like Behdeinkhlam. Women wear multiple layers of cloth wrapped around the waist and torso, and often adorn themselves with heirloom jewellery passed down through generations.

Jaintia men, particularly during festive processions, wear traditional dhotis and headgear, often carrying symbolic items such as wooden clubs or flags during ceremonial dances. The attire is both symbolic and spiritual, reflecting the tribe’s devotion and cultural pride.

Traditional Garo attire stands out with its vibrant colours and intricate weaves. Garo women wear the Dakmanda, a handwoven wraparound skirt tied at the waist, often paired with a blouse and the Daksari, another length of cloth draped over the shoulder. Traditional jewellery made from beads, brass, and silver completes the look, especially during dances like Wangala.

Men wear the Nokma Chikna, a cloth tied around the waist, and often carry spears or horns during cultural performances. Feathered headgear, necklaces made of boar tusks, and traditional bags enhance the ceremonial attire, which often signifies the wearer’s clan and status.

Belief & Religious Diversity

Meghalaya have largely embraced modern ways of living and modern belief systems, but they still identify with and honour the tribal traditions they come from.

The Khasis traditionally follow Niam Khasi, an indigenous faith centered on reverence for nature, ancestral spirits, and cosmic balance. The core philosophy is expressed in the triad: Tip Briew Tip Blei (Know Man, Know God), which emphasizes moral conduct, community harmony, and a deep connection between the human and the divine. Sacred forests (Law Kyntang), monoliths, and festivals like Shad Suk Mynsiem reflect this enduring worldview. While many Khasis have adopted Christianity, rituals such as offerings to ancestral spirits, respect for matrilineal customs, and sacred dances are still practiced and preserved, especially in rural areas and by adherents of the Seng Khasi movement.

In the Jaintia Hills, the Niamtre faith guides the spiritual life of many Jaintias. Rooted in a matrilineal structure, Niamtre blends animism with ancestral worship and the veneration of natural elements like rivers, hills, and sacred groves. Ritual specialists, or priests known as Lyngdoh, conduct seasonal rites and clan-based ceremonies. Festivals like Behdeinkhlam, a vibrant and symbolic event, aim to drive away disease and misfortune while strengthening social bonds. Although a significant number of Jaintias have embraced Christianity, traditional practices remain deeply embedded in community life, often coexisting with modern religious beliefs.

In the Garo Hills, the indigenous religion known as Songsarek (or Song-Dokgipa) continues to be observed by many. It centers on worshipping nature spirits (Misi Saljong, Tatara Rabuga, and others) and maintaining harmony between the seen and unseen worlds. The rituals are often conducted by a village priest or Nokma, who serves as both a spiritual and administrative leader. Offerings are made to appease forest spirits and protect communities from illness and misfortune. Despite the spread of Christianity, which is now the dominant faith among the Garos, the Songsarek revival movement is gaining momentum, particularly in rural pockets, where the younger generation seeks to reconnect with ancestral practices and oral traditions.

Meghalaya have largely embraced modern ways of living and modern belief systems, but they still identify with and honour the tribal traditions they come from.

The Khasis traditionally follow Niam Khasi, an indigenous faith centered on reverence for nature, ancestral spirits, and cosmic balance. The core philosophy is expressed in the triad: Tip Briew Tip Blei (Know Man, Know God), which emphasizes moral conduct, community harmony, and a deep connection between the human and the divine. Sacred forests (Law Kyntang), monoliths, and festivals like Shad Suk Mynsiem reflect this enduring worldview. While many Khasis have adopted Christianity, rituals such as offerings to ancestral spirits, respect for matrilineal customs, and sacred dances are still practiced and preserved, especially in rural areas and by adherents of the Seng Khasi movement.

In the Jaintia Hills, the Niamtre faith guides the spiritual life of many Jaintias. Rooted in a matrilineal structure, Niamtre blends animism with ancestral worship and the veneration of natural elements like rivers, hills, and sacred groves. Ritual specialists, or priests known as Lyngdoh, conduct seasonal rites and clan-based ceremonies. Festivals like Behdeinkhlam, a vibrant and symbolic event, aim to drive away disease and misfortune while strengthening social bonds. Although a significant number of Jaintias have embraced Christianity, traditional practices remain deeply embedded in community life, often coexisting with modern religious beliefs.

In the Garo Hills, the indigenous religion known as Songsarek (or Song-Dokgipa) continues to be observed by many. It centers on worshipping nature spirits (Misi Saljong, Tatara Rabuga, and others) and maintaining harmony between the seen and unseen worlds. The rituals are often conducted by a village priest or Nokma, who serves as both a spiritual and administrative leader. Offerings are made to appease forest spirits and protect communities from illness and misfortune. Despite the spread of Christianity, which is now the dominant faith among the Garos, the Songsarek revival movement is gaining momentum, particularly in rural pockets, where the younger generation seeks to reconnect with ancestral practices and oral traditions.

Cultural Etiquette

The residents of Meghalaya are diligent about their cleanliness drives and are proud of the recognition their efforts have earned. The communities also closely identify themselves with nature and worshipping nature is seen among the animist believers. Ancient wisdom has taught the land and its people the practice of sustainability and far-sightedness that continues to be in the people’s favour even today. Nature is deemed an invaluable resource and the most prized inheritance from our ancestors, which is why the people of Meghalaya treat it with utmost respect.

Speaking of respect, nothing shows it more than a visitor making the effort to converse with the locals in their language. “Kumno” means “hello”, “Bah” and “Kong” are terms of respect used when addressing male and female elders respectively, and “Khublei shibun” means “thank you very much”. Use these correctly and frequently, and you’ll leave with more memories than most visitors do.

The residents of Meghalaya are diligent about their cleanliness drives and are proud of the recognition their efforts have earned. The communities also closely identify themselves with nature and worshipping nature is seen among the animist believers. Ancient wisdom has taught the land and its people the practice of sustainability and far-sightedness that continues to be in the people’s favour even today. Nature is deemed an invaluable resource and the most prized inheritance from our ancestors, which is why the people of Meghalaya treat it with utmost respect.

Speaking of respect, nothing shows it more than a visitor making the effort to converse with the locals in their language. “Kumno” means “hello”, “Bah” and “Kong” are terms of respect used when addressing male and female elders respectively, and “Khublei shibun” means “thank you very much”. Use these correctly and frequently, and you’ll leave with more memories than most visitors do.